- Joined

- Jun 14, 2016

- Messages

- 263

- Reaction score

- 518

All images have been sourced from copyright free, public use image websites or used under fair use guidelines, as they best illustrate the article content.

If you’ve been an aquarist for any amount of time, chances are, you’ve lost a fish. It’s a painful and traumatic experience, especially when an aquarist has worked hard to ensure an exciting species’ survival. Sometimes, fish die with little warning. We come home one day, stare into our reef, only to notice that someone is missing. After some close inspection, the remains of a prized fish are discovered and the reality of fish-loss sets in. Yet sometimes a fish dies during what is a slow and painful process, especially difficult to watch. This can be a reoccurring parasitic infection, bacterial infection or just a long-term instance of refusing to eat. Most of us turn to hospital tanks, allowing for a host of treatment options and potentially curtailing the spread of disease. Even under the best circumstances and treatment, fish sometimes don’t fare well and continue an abrupt decline.

Like other reef aquarists, I have stared at a sick fish and wondered if it didn’t deserve the same compassion afforded other household pets. To be quickly and painlessly relieved of sickness and given an abrupt demise, free of long-term suffering. Euthanasia among pets is common but remains controversial and euthanasia for sick and dying people is taboo. Proponents of euthanasia point toward long-term illnesses that greatly reduce quality of life, are incurable and will eventually lead to death. Most veterinarians suggest euthanasia for household pets that have a dim chance of recovery and are likely to suffer during their last month’s alive. For aquarists, it begs the question, do our fish deserve a painless and immediate relief from incurable disease? Also, by euthanizing sick fish are we greatly reducing the probability that another species within our tank will fall ill?

The dilemma:

When you take a dog, cat or other common pet to the veterinarian, highly trained doctors have the resources to perform a battery of tests. Without any mystery, an illness can be diagnosed and treatment administered. Both the experience and training of the vet can be invaluable when making a prediction about how your pet’s disease will progress. Have they simply outlived their natural lifespan, or are they suffering from something incurable and debilitating? Even in worst case scenarios, a veterinarian can often provide multiple options. Animals can be kept comfortable for the remainder of life, or certain treatments can rebuild some quality of life and make for a better existence. Veterinarians have access to a whole host of medical technology, medications and procedures well out of reach for the common pet owner. If the decision to euthanize is made, it’s done in a controlled environment, under the supervision of a medical doctor using approved euthanasia drugs, known to cause a peaceful and painless death.

All of that is lost when a home aquarist tries to decide if a fish is beyond saving. Some aquarists buffer this blunt reality of fish-keeping by leaning back on the adage, “fish can’t feel pain.” However, recent breakthroughs in animal science and the ethos surrounding animal husbandry has shown that fish do in fact feel pain, along with a wide range of complex emotions. It’s quite possible when your fish stares up at you with fear, intimidation and pain, it’s those very emotions that it’s feeling. This means that our actions in treating, keeping and euthanizing a fish have a wide range of implications. In my view as a long-time reef aquarist, fish should be given the same sort of consideration that all companion animals are. Since few veterinarians’ service marine fish, it’s more than likely impossible to provide our piscine pets with that equal standard of care. That alone may disqualify fish from being “morally euthanized.” Can any aquarist, even an advanced one, really make judgement calls that determine whether a fish will recover from disease, or simply suffer until they die.

Most aquarists lack the resources to test for bacterial infections, determine the cause of tumors or determine the degree of infection present within a fish. Without those tools, we are left to educated guesswork. It’s very possible that an aquarist could accidently euthanize a fish which under the right care, would make a full recovery. We also cannot directly understand the nature of how much a fish is suffering. As I said earlier, scientists have shown that fish are far more emotionally complex than we once thought, but it’s also well known that they feel and interpret emotions and pain, very differently from other animals. It is possible an injury or behavior in a fish makes us believe they are gravely ill, when in fact a simple environmental change can make them better.

For these reasons, it’s hard as an aquarist to recommend or even justify euthanasia in our marine fish. I know several aquarists who have euthanized fish, really believing they were doing the right thing. However, when they described their fish’s symptoms to me, I was confident that the specimen was suffering from a common, treatable malady. Considering there is no second chance with euthanasia, it’s vital to be certain it’s the only option left for a sick animal. Fish are resilient and often if stressors are removed and treatment is provided, their condition will improve. Since most of our fish come from the wild, it’s not a positive practice to euthanize a fish when it becomes ill. A better choice is to research and educate ourselves as aquarists, so that we know how to act if a fish gets sick and know what species are unlikely to adapt to captivity.

Resilience:

As I mentioned, fish are resilient. The best illustration I can think of to show this, is a story from my personal reef tank. The tank, a 250 gallon reef, was home to a pair of Australian wide bar clownfish. Since they rarely strayed from a rose bubble tipped anemone, I thought I could safely add a pair of ORA nebula clownfish. I found a proven breeding pair (which commanded a hefty price) and after quarantine added them to the display. For the first several weeks, everything went swimmingly (no pun intended). The clowns set up shop on opposite sides of the aquarium and rarely entered each other’s territory. After several months, the dichotomy between the two-species changed. The smaller Nebula male was being badly harassed by the larger Australian male.

Hoping it was a minor territorial dispute, I left the fish alone, believing that perhaps they would settle their differences. Yet, the harassment went on. One day, after returning from my office, I found the Nebula male sulking in the upper corner of the aquarium. He was badly injured, with ragged fins and noticeable marks along his body. The fish was so stressed, he was unable to swim correctly and corkscrewed around the tank, nearly getting caught in a circulation pump. Every instinct told me that this fish was beyond help and that within a short period, would be dead. One area along his side was badly damaged, sporting a deep, gaping wound.

Rather than give up on him, I placed him in a hospital tank and began treatment with an antibiotic (to prevent infection) and a compound to aid in healing the damaged area. It took several days for the fish to show improvement, but within ten-days he was accepting food, swimming around and his vibrant color had returned. Not long after, he made a full recovery and once he was placed in a separate tank with his partner, has gone on to live a normal life.

I have little doubt that many aquarists would have considered this fish a lost cause. He was so weak when I removed him, that I simply dipped my cupped hand into the water and easily pulled him out. If euthanasia based on symptoms were used on this specimen, a healthy, colorful and rare fish would have been lost, simply due to an easily treated, environmental stress based malady.

Often, we think of our fish as weak. They tend to come down with parasitic infections, struggle to adapt to environmental changes and sometimes fail to adapt to captive life. Yet, fish are far from weak and in fact are marvels of evolution. They have a host of adaptations that make them strong, resilient and powerful survivors. For a fish to get sick, some condition within the aquarium must be totally out of whack or the stress of capture and shipping had to be unusually great. Often when simple parasitic infections kill fish, they receive little or no treatment and are left without quarantine or hospital tanks to rescue them from infected water. This is not because fish are weak, but because they are captured, shipped and kept in sub-par conditions that would be insufficient for any animal.

Fish are quite capable of recovering from illness and injury and aren’t likely (given the proper conditions) to simply suffer and die. Euthanasia could very well cut a fish’s life short, without offering it the right treatment to get better.

When it does happen:

All those things explained, there are times that fish end-up in very poor health and it’s not the result of a sub-par environment. It could be a seemingly un-curable infection or the result of an unexpected injury. Years ago, a Harlequin tusk-fish in one of my old tanks jumped out, falling about five and a half feet onto a tile floor. I found him a while later and he had been out of the water long enough that he was beginning to dry-out. When placed the fish in a hospital tank, it appeared unlikely it would recover. Yet, to my surprise, several weeks later he seemed alright.

Even though the fish was eating, it wasn’t gaining weight. Within several months, the tusk-fish appeared gaunt and un-easy in the tank. I provided a variety of treatment, but it became clear that something severely was wrong with this specimen. My guess, still today, as that during his epic fall an internal organ was badly damaged and couldn’t recover. Even with more aggressive treatment, the fish continued to fail, until it wouldn’t leave a rock outcropping and its breathing accelerated uncomfortably. At times, the tusk-fish would thrash around, as though it was in excoriating pain. Not long after, it was dead.

While I didn’t euthanize the fish, looking back on the scenario, it would have been a candidate for the procedure. It seemed impossible that it would recover from whatever injury it suffered. The time from the start of decline to death was long, meaning it’s possible the fish suffered for an indeterminate amount of time. Its outward behavior led me to believe it was in pain, scared and full of stress. A long time period of suffering compiled with no chance of recovery would qualify nearly any companion pet for euthanasia.

It’s only reality that many aquarists will find themselves in a similar circumstance and they may make the decision to euthanize a specimen. So how can it be done, safely and painlessly? Many suggestions have been made over the years, some as barbaric as smashing a fish with a blunt object and others more refined, yet still un-nerving, such as placing a fish in the freezer. The goal of euthanasia is to provide a peaceful and painless exit to this life. Usually, an animal is first placed into a deep sleep using powerful sedatives. Then a drug (often barbiturates) is administered the slows the heart and lungs, to the point that both eventually stop. It’s believed that the deep sleep provided by medical intervention ensures the animal doesn’t feel the sudden strangulation when vital organs begin to shut-down.

For a veterinarian, this is easily provided for companion animals, as doctors have access to a wide range of medicine. At home and working with a marine fish, often we are left without the tools to provide a dignified exit from suffering.

Often, I hear aquarists recommend an ice bath as a humane way to kill a fish. The belief that is exposure to increasingly cold temperatures simply causes a tropical fish’s body to slowly shut down. This may be true, but an ice bath is a painstaking process and has a varying degree of effectiveness on different species, often dictated by their resilience to low temperatures. Since this method could potentially cause un-due suffering and take more time than is humane, it shouldn’t be considered a viable, pain-less way to euthanize a fish.

I’ve also heard aquarists recommend placing a fish out of water, in the freezer. For humans, this could be compared to drowning in ice cold water. That is certainly not a pain-free and peaceful death and therefore should not be a method of euthanasia.

Properly euthanizing a fish takes a bit more work and more planning. It’s best to start the process 24-hours before the procedure, by withholding food from the species to be euthanized. This will ensure that life threatening medications will be assimilated faster, thus speeding up the process. Often, sick fish are not consuming food, so a fasting period may not be necessary.

It’s best to place the fish in a container of water, so that medicinal overload acts quickly and as painlessly as possible. I recommend a simple 1-3-gallon container. The drug of choice for piscine euthanasia is MS-222 which is also sold as methane sulfonate or under the common name tricaine s. Sometimes it is sold in pet stores under the name Finquel. Tricaine is used by aqua-culture facilities and research labs as a euthanasia agent for piscine life and has been approved by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) for this purpose. If an aquarist plans on implementing euthanasia when necessary, it’s best to always have some tricaine on hand.

Use a small container to mix some tank water with ten times the recommended dose of tricaine. Once the material has dissolved, quickly pour the contents into the container holding the dying fish. Tricaine, if used in too small an amount, can simply send a fish into unconsciousness, only to wake up after a period of 30 minutes to several hours. For this reason, it’s best to leave the fish for 30 minutes, to ensure that the medicine has killed it. At this point, discard the fish and all medicated water. Also ensure that tricaine is kept away from children and in a safe place.

Some aquarists recommend clove oil in lieu of tricaine, at a dosage of 50 drops per gallon of water. While it will most certainly kill a sick fish, the reaction of fish euthanized with clove oil leads me to believe the oil causes a severe burning of the gills. This of course fails the ethos of euthanasia, which is to provide a quick, painless and peaceful death. For that reason, I don’t recommend it.

A last resort:

I don’t personally recommend euthanasia for any but the most advanced and well equipped marine aquarists. The clear majority of aquarists simply don’t have the knowledge or resources on hand to decide when a fish is beyond repair and in pain. Even for advanced aquarists, euthanasia should not be taken lightly and only considered when every treatment option has been exhausted.

If you’ve been an aquarist for any amount of time, chances are, you’ve lost a fish. It’s a painful and traumatic experience, especially when an aquarist has worked hard to ensure an exciting species’ survival. Sometimes, fish die with little warning. We come home one day, stare into our reef, only to notice that someone is missing. After some close inspection, the remains of a prized fish are discovered and the reality of fish-loss sets in. Yet sometimes a fish dies during what is a slow and painful process, especially difficult to watch. This can be a reoccurring parasitic infection, bacterial infection or just a long-term instance of refusing to eat. Most of us turn to hospital tanks, allowing for a host of treatment options and potentially curtailing the spread of disease. Even under the best circumstances and treatment, fish sometimes don’t fare well and continue an abrupt decline.

Like other reef aquarists, I have stared at a sick fish and wondered if it didn’t deserve the same compassion afforded other household pets. To be quickly and painlessly relieved of sickness and given an abrupt demise, free of long-term suffering. Euthanasia among pets is common but remains controversial and euthanasia for sick and dying people is taboo. Proponents of euthanasia point toward long-term illnesses that greatly reduce quality of life, are incurable and will eventually lead to death. Most veterinarians suggest euthanasia for household pets that have a dim chance of recovery and are likely to suffer during their last month’s alive. For aquarists, it begs the question, do our fish deserve a painless and immediate relief from incurable disease? Also, by euthanizing sick fish are we greatly reducing the probability that another species within our tank will fall ill?

The dilemma:

When you take a dog, cat or other common pet to the veterinarian, highly trained doctors have the resources to perform a battery of tests. Without any mystery, an illness can be diagnosed and treatment administered. Both the experience and training of the vet can be invaluable when making a prediction about how your pet’s disease will progress. Have they simply outlived their natural lifespan, or are they suffering from something incurable and debilitating? Even in worst case scenarios, a veterinarian can often provide multiple options. Animals can be kept comfortable for the remainder of life, or certain treatments can rebuild some quality of life and make for a better existence. Veterinarians have access to a whole host of medical technology, medications and procedures well out of reach for the common pet owner. If the decision to euthanize is made, it’s done in a controlled environment, under the supervision of a medical doctor using approved euthanasia drugs, known to cause a peaceful and painless death.

All of that is lost when a home aquarist tries to decide if a fish is beyond saving. Some aquarists buffer this blunt reality of fish-keeping by leaning back on the adage, “fish can’t feel pain.” However, recent breakthroughs in animal science and the ethos surrounding animal husbandry has shown that fish do in fact feel pain, along with a wide range of complex emotions. It’s quite possible when your fish stares up at you with fear, intimidation and pain, it’s those very emotions that it’s feeling. This means that our actions in treating, keeping and euthanizing a fish have a wide range of implications. In my view as a long-time reef aquarist, fish should be given the same sort of consideration that all companion animals are. Since few veterinarians’ service marine fish, it’s more than likely impossible to provide our piscine pets with that equal standard of care. That alone may disqualify fish from being “morally euthanized.” Can any aquarist, even an advanced one, really make judgement calls that determine whether a fish will recover from disease, or simply suffer until they die.

Most aquarists lack the resources to test for bacterial infections, determine the cause of tumors or determine the degree of infection present within a fish. Without those tools, we are left to educated guesswork. It’s very possible that an aquarist could accidently euthanize a fish which under the right care, would make a full recovery. We also cannot directly understand the nature of how much a fish is suffering. As I said earlier, scientists have shown that fish are far more emotionally complex than we once thought, but it’s also well known that they feel and interpret emotions and pain, very differently from other animals. It is possible an injury or behavior in a fish makes us believe they are gravely ill, when in fact a simple environmental change can make them better.

For these reasons, it’s hard as an aquarist to recommend or even justify euthanasia in our marine fish. I know several aquarists who have euthanized fish, really believing they were doing the right thing. However, when they described their fish’s symptoms to me, I was confident that the specimen was suffering from a common, treatable malady. Considering there is no second chance with euthanasia, it’s vital to be certain it’s the only option left for a sick animal. Fish are resilient and often if stressors are removed and treatment is provided, their condition will improve. Since most of our fish come from the wild, it’s not a positive practice to euthanize a fish when it becomes ill. A better choice is to research and educate ourselves as aquarists, so that we know how to act if a fish gets sick and know what species are unlikely to adapt to captivity.

Resilience:

As I mentioned, fish are resilient. The best illustration I can think of to show this, is a story from my personal reef tank. The tank, a 250 gallon reef, was home to a pair of Australian wide bar clownfish. Since they rarely strayed from a rose bubble tipped anemone, I thought I could safely add a pair of ORA nebula clownfish. I found a proven breeding pair (which commanded a hefty price) and after quarantine added them to the display. For the first several weeks, everything went swimmingly (no pun intended). The clowns set up shop on opposite sides of the aquarium and rarely entered each other’s territory. After several months, the dichotomy between the two-species changed. The smaller Nebula male was being badly harassed by the larger Australian male.

Hoping it was a minor territorial dispute, I left the fish alone, believing that perhaps they would settle their differences. Yet, the harassment went on. One day, after returning from my office, I found the Nebula male sulking in the upper corner of the aquarium. He was badly injured, with ragged fins and noticeable marks along his body. The fish was so stressed, he was unable to swim correctly and corkscrewed around the tank, nearly getting caught in a circulation pump. Every instinct told me that this fish was beyond help and that within a short period, would be dead. One area along his side was badly damaged, sporting a deep, gaping wound.

Rather than give up on him, I placed him in a hospital tank and began treatment with an antibiotic (to prevent infection) and a compound to aid in healing the damaged area. It took several days for the fish to show improvement, but within ten-days he was accepting food, swimming around and his vibrant color had returned. Not long after, he made a full recovery and once he was placed in a separate tank with his partner, has gone on to live a normal life.

I have little doubt that many aquarists would have considered this fish a lost cause. He was so weak when I removed him, that I simply dipped my cupped hand into the water and easily pulled him out. If euthanasia based on symptoms were used on this specimen, a healthy, colorful and rare fish would have been lost, simply due to an easily treated, environmental stress based malady.

Often, we think of our fish as weak. They tend to come down with parasitic infections, struggle to adapt to environmental changes and sometimes fail to adapt to captive life. Yet, fish are far from weak and in fact are marvels of evolution. They have a host of adaptations that make them strong, resilient and powerful survivors. For a fish to get sick, some condition within the aquarium must be totally out of whack or the stress of capture and shipping had to be unusually great. Often when simple parasitic infections kill fish, they receive little or no treatment and are left without quarantine or hospital tanks to rescue them from infected water. This is not because fish are weak, but because they are captured, shipped and kept in sub-par conditions that would be insufficient for any animal.

Fish are quite capable of recovering from illness and injury and aren’t likely (given the proper conditions) to simply suffer and die. Euthanasia could very well cut a fish’s life short, without offering it the right treatment to get better.

When it does happen:

All those things explained, there are times that fish end-up in very poor health and it’s not the result of a sub-par environment. It could be a seemingly un-curable infection or the result of an unexpected injury. Years ago, a Harlequin tusk-fish in one of my old tanks jumped out, falling about five and a half feet onto a tile floor. I found him a while later and he had been out of the water long enough that he was beginning to dry-out. When placed the fish in a hospital tank, it appeared unlikely it would recover. Yet, to my surprise, several weeks later he seemed alright.

Even though the fish was eating, it wasn’t gaining weight. Within several months, the tusk-fish appeared gaunt and un-easy in the tank. I provided a variety of treatment, but it became clear that something severely was wrong with this specimen. My guess, still today, as that during his epic fall an internal organ was badly damaged and couldn’t recover. Even with more aggressive treatment, the fish continued to fail, until it wouldn’t leave a rock outcropping and its breathing accelerated uncomfortably. At times, the tusk-fish would thrash around, as though it was in excoriating pain. Not long after, it was dead.

While I didn’t euthanize the fish, looking back on the scenario, it would have been a candidate for the procedure. It seemed impossible that it would recover from whatever injury it suffered. The time from the start of decline to death was long, meaning it’s possible the fish suffered for an indeterminate amount of time. Its outward behavior led me to believe it was in pain, scared and full of stress. A long time period of suffering compiled with no chance of recovery would qualify nearly any companion pet for euthanasia.

It’s only reality that many aquarists will find themselves in a similar circumstance and they may make the decision to euthanize a specimen. So how can it be done, safely and painlessly? Many suggestions have been made over the years, some as barbaric as smashing a fish with a blunt object and others more refined, yet still un-nerving, such as placing a fish in the freezer. The goal of euthanasia is to provide a peaceful and painless exit to this life. Usually, an animal is first placed into a deep sleep using powerful sedatives. Then a drug (often barbiturates) is administered the slows the heart and lungs, to the point that both eventually stop. It’s believed that the deep sleep provided by medical intervention ensures the animal doesn’t feel the sudden strangulation when vital organs begin to shut-down.

For a veterinarian, this is easily provided for companion animals, as doctors have access to a wide range of medicine. At home and working with a marine fish, often we are left without the tools to provide a dignified exit from suffering.

Often, I hear aquarists recommend an ice bath as a humane way to kill a fish. The belief that is exposure to increasingly cold temperatures simply causes a tropical fish’s body to slowly shut down. This may be true, but an ice bath is a painstaking process and has a varying degree of effectiveness on different species, often dictated by their resilience to low temperatures. Since this method could potentially cause un-due suffering and take more time than is humane, it shouldn’t be considered a viable, pain-less way to euthanize a fish.

I’ve also heard aquarists recommend placing a fish out of water, in the freezer. For humans, this could be compared to drowning in ice cold water. That is certainly not a pain-free and peaceful death and therefore should not be a method of euthanasia.

Properly euthanizing a fish takes a bit more work and more planning. It’s best to start the process 24-hours before the procedure, by withholding food from the species to be euthanized. This will ensure that life threatening medications will be assimilated faster, thus speeding up the process. Often, sick fish are not consuming food, so a fasting period may not be necessary.

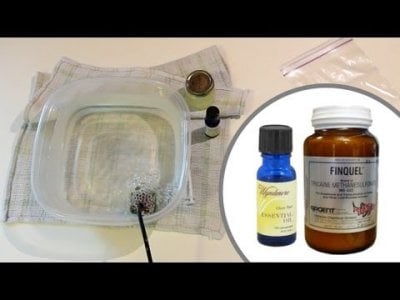

It’s best to place the fish in a container of water, so that medicinal overload acts quickly and as painlessly as possible. I recommend a simple 1-3-gallon container. The drug of choice for piscine euthanasia is MS-222 which is also sold as methane sulfonate or under the common name tricaine s. Sometimes it is sold in pet stores under the name Finquel. Tricaine is used by aqua-culture facilities and research labs as a euthanasia agent for piscine life and has been approved by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) for this purpose. If an aquarist plans on implementing euthanasia when necessary, it’s best to always have some tricaine on hand.

Use a small container to mix some tank water with ten times the recommended dose of tricaine. Once the material has dissolved, quickly pour the contents into the container holding the dying fish. Tricaine, if used in too small an amount, can simply send a fish into unconsciousness, only to wake up after a period of 30 minutes to several hours. For this reason, it’s best to leave the fish for 30 minutes, to ensure that the medicine has killed it. At this point, discard the fish and all medicated water. Also ensure that tricaine is kept away from children and in a safe place.

Some aquarists recommend clove oil in lieu of tricaine, at a dosage of 50 drops per gallon of water. While it will most certainly kill a sick fish, the reaction of fish euthanized with clove oil leads me to believe the oil causes a severe burning of the gills. This of course fails the ethos of euthanasia, which is to provide a quick, painless and peaceful death. For that reason, I don’t recommend it.

A last resort:

I don’t personally recommend euthanasia for any but the most advanced and well equipped marine aquarists. The clear majority of aquarists simply don’t have the knowledge or resources on hand to decide when a fish is beyond repair and in pain. Even for advanced aquarists, euthanasia should not be taken lightly and only considered when every treatment option has been exhausted.