Coral Coloration: Proteins and Chromoproteins

It is well known that corals get their color from the Zooxanthellae in their cells, however, an often overlooked but very important aspect of coral coloration are fluorescent proteins and non-fluorescent chromoproteins. There have been some great write-ups about these other aspects of color coloration by people like Dana Riddle, but I feel that in this hobby you can never have too much information and I wanted to help distill down some of the concepts that are not very well understood by many hobbyists.

So what gives a coral its color?

Coral coloration, for obvious reasons, is one of the most talked-about and least understood aspects of coral health and biology. The hundreds of complex chemical reactions happening within corals that give them their color are widely credited to the Zooxanthellae algae that lives inside of the cells of coral. While a large chunk of coral coloration does come from this algae, the most brilliant expressions of color are typically made by the coral itself. For the most part, there are two proteins that corals produce for color expression, Fluorescent proteins and Chromoproteins. While there are hundreds of proteins involved in various color production, the important aspect of these proteins is that they require particular light spectrums in order to be activated or excited.

Why are some corals more colorful than others?

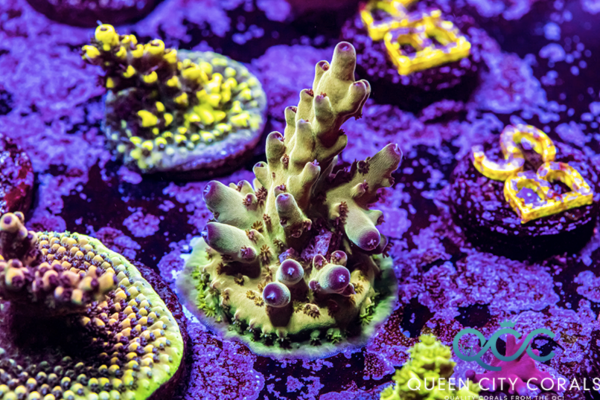

One very interesting aspect of these proteins is the variation across different coral species. For instance, according to the article, Expansion and Diversification of Fluorescent Protein Genes in Fifteen Acropora Species during the Evolution of Acroporid Corals, across the 15 species of Acropora, they found each species has 9-18 different fluorescent proteins genes and an average of 14. Compared to the two different Montipora species they studied which each only had 2 fluorescent protein genes. This is likely why we see so many rainbow Acroporas and so few rainbow Monitporas, this also accounts for why some species of Acropora, such as Acropora Tenuis, have tons of strains with wildly different colors.

Why do the nicest corals always seem to go first?

Everyone who’s had a tank crash knows that it's almost always your favorite, most expensive piece that dies first but why is that? If something is bothering one specific type of coral shouldn’t it affect all of them? There are two very interesting studies that might explain this phenomenon. The first, Fluorescent protein expression in temperature tolerant and susceptible reef-building corals which exposed a wide variety of corals to 28 °C (82.4 °F) and 31 °C (87.8 °F). They showed that Acropora, Montipora, Favites, and Birdsnest corals with different Fluorescent Proteins had different bleaching rates amongst the same species. These results can also be seen in the natural environment. The article Color morphs of the coral, Acropora tenuis, show different responses to environmental stress and different expression profiles of fluorescent-protein genes observed that during one bleaching event in Okinawa Prefecture during the summer of 2017 the Yellow-Green Acropora Tenuis specimens had no bleaching while brown and purple morphs had high levels of bleaching and a 10-15% of brownish morph died.

These articles may suggest that the hobby’s most colorful corals are also at the highest risk during stressful events. This could be due to higher levels of fluorescent and chromoprotein present in these corals. The higher protein production in these corals could correlate to higher energy consumption as well.

Higher energy usage for more chromoproteins

How do you get the best colors out of your coral?

I’d love to tell you that there’s one simple trick to get great coral color, unfortunately like with most things in this hobby, it's a little more complicated than that. The first factor is, as I discussed above, different species and even different corals within a species, have wildly different Fluorescent Proteins and Chromoproteins. Due to these differences,you won’t be able to get every color out of every coral; you can however bring out some colors that you may not have seen before. The way to do this would be experimenting with new lightings, different pH levels, and different temperatures. But make sure to only change one variable at a time and do it slowly. At the end of the day, this should be a last resort because most corals look the best when they are happy and healthy.

Brighter isn’t always better!

Most people know that when corals are under severe stress they can bleach, what this means is that they expel all of their Zooxanthellae algae in order to try and survive, while this most commonly happens in the wild due to high temperatures it can also be caused by a number of changes in the aquarium from lighting to pH, however, most corals will not just turn white and according to Fluorescent protein expression in temperature tolerant and susceptible reef-building corals, these bleached corals may even get brighter. They found that in one coral that was subjected to 32 C (90 F) the green fluorescent protein increased 134 fold after 24 hours suggesting that it became much brighter and may have appeared more desirable to many hobbyists, unfortunately, this did not last after 72 hours had decreased .004 fold.

This is important because I have seen many people try and purchase an extremely bright coral that may look fine at first but is in fact, extremely bleached and likely will not recover unless it is given plenty of food and whatever variable is causing the stress is removed. Make sure that when you're looking at a coral there isn’t any white tissue that may be an indication of bleaching and if this begins to happen to one of your corals it may be good to move it to a shady spot in your tank and feed it slowly and regularly in order supplement the nutrients that the Zooxanthellae would normally provide.

What does this mean to you?

Like most informational articles, this means very little in terms of your day-to-day reef keeping, however, my goal of this article is to help hobbyists understand what really causes the colors we see when we look at our tank. These colors have nothing to do with the actual husbandry of our coral and yet they are one of the most important things we focus on when purchasing corals. A brown Acropora might be the healthiest piece in the world but it will only sell for a fraction of what a rainbow Tenuis that might be slightly bleached will sell for.

This is not to say that is wrong, but rather to illustrate the importance we place on coloration that many (including myself until recently) do not fully understand. For instance, I could have told you the exact range parameters that will make most corals happy, but they might look dull. I hope that I have been able to outline how you can improve coral coloration, without sacrificing husbandry. The most important aspect of any coral is health because no matter how bright an Acro or Acan is, it won’t look good when it's just a white skeleton.

References:

Dizon, Exequiel Gabriel, et al. “Fluorescent Protein Expression in Temperature Tolerant and Susceptible Reef-Building Corals.” Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, vol. 101, no. 1, 2 Mar. 2021, pp. 71–80., https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025315421000059.

Kashimoto, Rio, et al. “Expansion and Diversification of Fluorescent Protein Genes in Fifteen Acropora Species during the Evolution of Acroporid Corals.” Genes, vol. 12, no. 3, 2021, p. 397., https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12030397.

Noriyuki Satoh, Koji Kinjo, Kohei Shintaku, Daisuke Kezuka, Hiroo Ishimori, Atsushi Yokokura, Kazutaka Hagiwara, Kanako Hisata, Mayumi Kawamitsu, Koji Koizumi, Chuya Shinzato, Yuna Zayasu, Color morphs of the coral, Acropora tenuis, show different responses to environmental stress and different expression profiles of fluorescent-protein genes, G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics, Volume 11, Issue 2, February 2021, jkab018, https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkab018

Riddle, Dana. “Help! My Corals Are Changing Colors.” MACNA 2018. MACNA, Sept. 2018, Las Vegas.